| SELECTING THE RIGHT ANCHOR |

|

|

Anchor

An anchor is a device, normally made of metal, used to connect a vessel to the bed of a body of water to prevent the craft from drifting due to wind or current. The word derives from Latin ancora, which itself comes from the Greek ἄγκυρα (ankura).

Anchors can either be temporary or permanent. Permanent anchors are used in the creation of a mooring, and are rarely moved; a specialist service is normally needed to move or maintain them. Vessels carry one or more temporary anchors, which may be of different designs and weights.

A sea anchor is a drogue, not in contact with the seabed, used to control a drifting vessel.

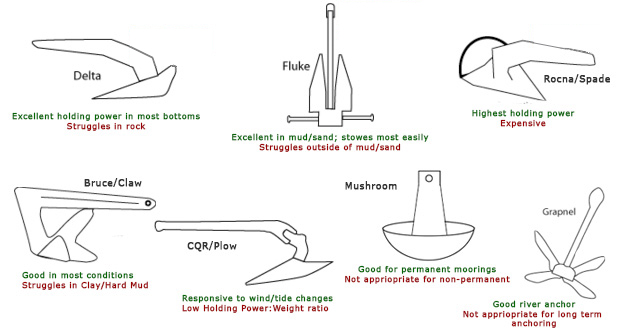

Selecting the Right Anchor

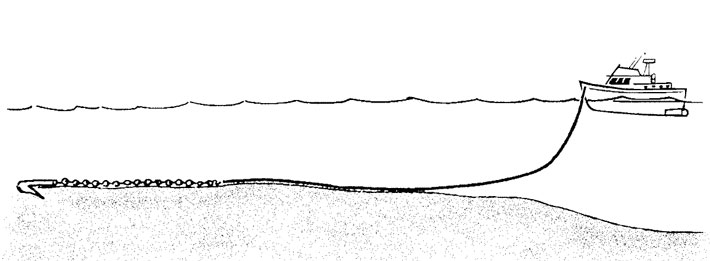

“What is the best kind of anchor and rode for my boat?” We get asked that question a lot, and the answer is often “more than one anchor, of different types.” While you might wonder if we are just trying to sell a few more anchors, the experts generally agree with this viewpoint. The type of bottom—mud, grass, sand, coral or rock—will dictate different choices of anchors, as will the size and windage of the boat, the wind conditions and the seastate.

Small boat anchors

Until the mid-20th century, anchors for smaller vessels were either scaled-down versions of admiralty anchors, or simple grapnels. As new designs with greater holding-power-to-weight ratios, a great variety of anchor designs has emerged. Many of these designs are still under patent, and other types are best known by their original trademarked names.

Grapnel anchor

A traditional design, the grapnel is merely a shank with four or more tines. It has a benefit in that, no matter how it reaches the bottom, one or more tines will be aimed to set. In coral, or rock, it is often able to set quickly by hooking into the structure, but may be more difficult to retrieve. A grapnel is often quite light, and may have additional uses as a tool to recover gear lost overboard. Its weight also makes it relatively easy to move and carry, however its shape is generally not very compact and it may be awkward to stow unless a collapsing model is used.

Grapnels rarely have enough fluke area to develop much hold in sand, clay, or mud. It is not unknown for the anchor to foul on its own rode, or to foul the tines with refuse from the bottom, preventing it from digging in. On the other hand, it is quite possible for this anchor to find such a good hook that, without a trip line from the crown, it is impossible to retrieve.

Herreshoff anchor

This is essentially the same pattern as an admiralty anchor, albeit with small diamond shaped flukes or palms. The novelty of the design lay in the means by which it could be broken down into three pieces for stowage. In use, it still presents all the issues of the admiralty pattern anchor.

Northill anchor

Originally designed as a lightweight anchor for seaplanes, this design consists of two plough-like blades mounted to a shank, with a folding stock crossing through the crown of the anchor.

CQR (secure) plough anchor

Ploughs are popular with cruising sailors and other private boaters. They are generally good in all bottoms, but not exceptional in any. The CQR design has a hinged shank. Despite the widely held belief that this is to allow the anchor to turn with direction changes rather than breaking out, the actual purpose is to prevent the weight of the shank from negatively impacting the fluke's orientation while setting. Other plough types have a rigid shank. Plough anchors are usually stowed in a roller at the bow.

Owing to the use of lead or other dedicated tip-weight, the plough is heavier than average for the amount of resistance developed, and may take more careful technique and a longer period to set thoroughly. It cannot be stored in a hawsepipe.

Danforth anchor

Tripping palms at the crown act to tip the flukes into the seabed. The design is a burying variety, and once well set can develop high resistance. Its lightweight and compact flat design make it easy to retrieve and relatively easy to store; some anchor rollers and hawsepipes can accommodate a fluke-style anchor.

A Danforth will not usually penetrate or hold in gravel or weeds. In boulders and coral it may hold by acting as a hook. If there is much current, or if the vessel is moving while dropping the anchor, it may "kite" or "skate" over the bottom due to the large fluke area acting as a sail or wing.

The Fortress is an aluminum alloy Danforth variant. This anchor can be disassembled for storage and it features an adjustable 32° and 45° shank/fluke angle to improve holding capability in common sea bottoms such as hard sand and soft mud.

Hall anchor

A Hall anchor is a commonly used conventional stockless anchor found throughout the commercial shipping industry. The traditional design and proven performance makes the Hall anchor an attractive anchor for your ship. The Hall anchor is stowed against the shell or frog eye.

Bruce or claw anchor

The Bruce and its copies, known generically as "claws", have become a popular option for small boaters. It was intended to address some of the problems of the only general-purpose option then available, the plough. Claw-types set quickly in most seabeds and although not an articulated design, they have the reputation of not breaking out with tide or wind changes, instead slowly turning in the bottom to align with the force.

Claw types have difficulty penetrating weedy bottoms and grass. They offer a fairly low holding-power-to-weight ratio and generally have to be oversized to compete with newer types. On the other hand, they have a good reputation in boulder bottoms, perform relatively well with low rode scopes and set fairly reliably. They cannot be used with hawsepipes.

Admiralty anchor

The Admiralty pattern anchor is the most recognisable as a typical anchor of a sailing ship. Developed in 1841 under the guidance of Admiral Sir William Parker it had a wooded shock, later to be wrought iron and with curved arms. The end of the 19th century saw the patenting of the new type of anchor – the stockless anchor. The type that remains in use on board sailing ships to this day.

Mushroom anchor

The mushroom anchor is suitable where the seabed is composed of silt or fine sand. It is shaped like an inverted mushroom, the head becoming buried in the silt. A counterweight is often provided at the other end of the shank to lay it down before it becomes buried.

A mushroom anchor will normally sink in the silt to the point where it has displaced its own weight in bottom material, thus greatly increasing its holding power. These anchors are only suitable for a silt or mud bottom, since they rely upon suction and cohesion of the bottom material, which rocky or coarse sand bottoms lack. The holding power of this anchor is at best about twice its weight until it becomes buried, when it can be as much as ten times its weight.

What weight range fits my boat?

Choose an anchor that’s the right size for your boat and the locations and weather where you anchor. Take the anchor manufacturer’s suggested sizes into account and consider your boating style. Do you typically anchor for two hours or for two weeks, in a lake or in the Atlantic Ocean? The recommended anchor sizes from our Annual Catalog will work well for most boaters, under most conditions.

Sizing an anchor for your boat reinforces, with some limits, the “bigger is better” idea. If your engine fails and you are drifting toward a lee shore, having a properly sized anchor ready could save your boat. But raising the anchor by hand, with no electric powered windlass, calls for light and efficient ground tackle (and a strong back).

Products

SHACKLE for ANCHOR, 12 mm

01.080.12

POLYETHYLENE BUOY, 390 mm, RED

33.170.00RO

BOW ROLLER FOR SMALL VESSELS, S/S, 205 x 45 x 53 mm

01.118.80

STEAMHEAD ROLLER, S/S, 90 x 90 mm

01.349.00

|